What is chardonnay?

It really depends on who you ask, and where it's from. Adaptable and hearty chardonnay flourishes easily in most climates and conditions, making it one of the most widely-planted grape varieties on the globe, and planted in more wine regions than any other. The final results are a spectrum of flavours and styles – from pristine Blanc de Blancs Champagne to flinty and precise Chablis and from noble Burgundian heavyweights to creamy Californian ripeness and yes, even to lusciously sweet Canadian icewine.

With so many faces, guises and options, what is chardonnay? The grape itself is fairly neutral, owing a great deal of its flavour to vineyard and winemaking decisions. It’s a blank canvas for winemakers to colour and control – too oft, sadly, with overuse of wood. When oak isn’t allowed to overpower, the clean, crisp nature of the grape emerges. Cooler climates preserve this freshness and help balance the alcohol, which is naturally on the higher side. Higher altitude and latitude helps, as does aggressive pruning and canopy management. Clonal selection is key too, as there are dozens of clones, each with pros and cons to be matched to site. When yields are kept low and hands are kept at bay, chardonnay is a terroir transmitter. Chardonnay especially loves limestone and chalky soils – found in abundance in the grape’s traditional and glorious homeland of Chablis and Burgundy.

The name Chablis originates from two Celtic words: “cab” (house) and “leya” (near to the woods). Remnants from a Neolithic village, and later structures dating back to the Gauls show that humans lived in the area for centuries. Romans brought vines to Chablis between the 1st – 3rd Century, establishing vine growing and wine production before Cistercian Monks arrived in the 12th Century.

The northernmost wine district of Burgundy, Chablis is on the fringe of where chardonnay can ripen and thrive naturally. The continental climate contributes to wines with distinct acidity and purity of flavours and aromas, with warm summers and cold, often snowy winters. Sudden freezes in April or May pose a huge threat to budding or flowering vines; major efforts are made to mitigate frost damage and to heat the vineyards as soon as the threat of frost arises. Gas burning and oil vine heaters, chaufferettes, were first used in Chablis the 1950’s and are still in use in some low lying areas today, where fog threatens to pool. These heaters can help limit frost damage by maintaining temperatures above freezing even at -5°C. Spraying vines with water when temperatures drop is another method, creating a wee igloo around the vine bud. Naturally, both heating and spraying are costly measures, though not as pricey as hiring helicopters to hover over the vineyards to break up and warm frost-risk air – a practice among some producers.

Rolling hills and valleys extend out like a star from the town of Chablis, halved by the serenity of the River Serein. The river divides the region into two distinct parts: The Left Bank and the Right Bank. There are approximately 5400ha under vine divided amongst 350 growers and spread over approximately 20km from north to south and 15km from east to west. The Premier Cru and Grand Cru sites are clustered in the nexus of the star, with the seven contiguous Grand Cru climats hugging the right bank slope above Chablis.

Soils are key here, with the precisely delimitated climats mapped along the range of soil types and altitude. The notion of climats, the first written trace of which was scripted in Chablis (1540), is a shared ethos across Bourgogne and illustrate the inherent importance of the terroir. These named plots of vines have unique and subtle combinations of aspect, slope, elevation and soil geology, each transmitting a unique identity and character. In Chablis, 47 climat names can appear on wine labels; 40 for Premier Cru and seven for Grand Cru.

Chablis’ soils are located in a sedimentary basin. The main substrate is Jurassic limestone, specifically Kimmeridgian, dating back 150 million years and composed of tiny, comma-shaped fossilized oyster shells that once laid on the ocean floor. The premier and grand cru climats are located on these soft, chalky fossil-bearing Kimmerdidgian slopes, alternating with bands of gray marl. Hard calcareous limestone called Portlandian tops the plateaus, and are home to the Petit Chablis vineyards.

The Appellations & Their Wines

There are four appellations in Chablis: Petit Chablis, Chablis, Chablis Premier Cru and Chablis Grand Cru. Here is a brief overview, as well as wines we've recently tasted here at GOW, for your reference. Unfortunately the 2016 vintage was marred by very poor weather, so while quality remains high, quantity is way down. The vintage reportedly is approximately 50 percent of average quantity, making what few wines we are seeing on the shelves, higher than normal in price. Fortunately, 2015 and 2014 provided relatively good quantity, and good quality, so thee are reasonably healthy stock levels in some mature markets (read - not really BC).

Petit Chablis is planted almost exclusively on the hillside plateaus and on Portlandian soils. Fresh, crisp and with subtle white florals and salty minerality, these refreshing wines are meant to be enjoyed in their youth.

Chablis is the largest of the four appellations in terms of surface area and production, and thus has a wide range of styles based on age of vine and winemaker. They typically have greater structure than Petit Chablis, but still inherent drinkability in youth. The appellation village of Chablis is produced in the communes of Beines, Béru, Chablis, Fyé, Milly, Poinchy, La Chapelle-Vaupelteigne, Chemilly-sur-Serein, Chichée, Collan, Courgis, Fleys, Fontenay-Près-Chablis, Lignorelles, Ligny-le-Châtel, Maligny, Poilly-sur-Serein, Préhy, Villy and Viviers. In the Chablis appellation there are no named climats, though many lieu-dits (named sites).

Chablis Premier Cru is comprised of 40 climats, 17 of which are more commonly used as main climats. Each has its own style traversing from vibrant and mineral to delicate and fruity. They lie on sloping Kimmeridgian soils either side of the River Serein, with the most sought after climates resting on the right bank, encircling the Grand Crus. In youth, these wines are not as aromatic as Petit Chablis and Chablis, through with a few years age their well-built structure impresses. The main climats include Mont de Milieu, Montée de Tonerre, Fourchaume, Vaillons, Montmains, Côte de Léchet, Beauroy, Vaucoupin, Vosgros, Vau de Vey, Vau Ligneau, Beauregard and Fourneaux.

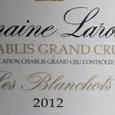

Chablis Grand Cru comprises the top sites of the region, and the heights of the quality pyramid. Seven contiguous climats arc along the right bank of the River Serein, directly north east of the town of Chablis. Vineyards face the sun at altitudes of 100-250 metres and exclusively on Kimmeridgian limestone and marls. The wines are very long-lived, with most starting to reach potential after 10-15 years of age. Intense minerality, flint, dried fruits, citrus and honey are hallmarks, as well as a striking balance between vibrant acidity and concentrated richness.

Each Grand Cru is defined by its own unique characteristics. From left to right:

Bougros – full bodied, robust, mineral and supple. Watch for the special ridge, Côte Bouguerots

Preuses – Very stony soils. long and noble, finessed, with exceptional aging capacity

Vaudésir – lively, floral, rounded and ripe, voluptuous

Grenouilles – floral, fruity, softer and richer in body. Grenouilles means frogs in French, referring to the closeness of this Grand Cru to the River Ser

Valmur – mineral, nervy, though fruity and very well balanced

Les Clos – mineral and powerful, big and chewy, with great aging potential

Blanchot – floral, supple and finessed, often subtle and easily appealing

quicksearch

quicksearch